516 lines

17 KiB

Markdown

516 lines

17 KiB

Markdown

---

|

||

title: Generating Random Poems with Python

|

||

layout: post

|

||

hidden: true

|

||

---

|

||

|

||

In this post, I will demonstrate how to generate random text using a few lines

|

||

of standard python and then progressively refine the output until it looks

|

||

poem-like.

|

||

|

||

If you would like to follow along with this post and run the code snippets

|

||

yourself, you can clone [my NLP repository](https://github.com/thallada/nlp/)

|

||

and run [the Jupyter

|

||

notebook](https://github.com/thallada/nlp/blob/master/edX%20Lightning%20Talk.ipynb).

|

||

|

||

You might not realize it, but you probably use an app everyday that can generate

|

||

random text that sounds like you: your phone keyboard.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Just by tapping the next suggested word over and over, you can generate text. So how does it work?

|

||

|

||

## Corpus

|

||

|

||

First, we need a **corpus**: the text our generator will recombine into new

|

||

sentences. In the case of your phone keyboard, this is all the text you've ever

|

||

typed into your keyboard. For our example, let's just start with one sentence:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

corpus = 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog'

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

## Tokenization

|

||

|

||

Now we need to split this corpus into individual **tokens** that we can operate

|

||

on. Since our objective is to eventually predict the next word from the previous

|

||

word, we will want our tokens to be individual words. This process is called

|

||

**tokenization**. The simplest way to tokenize a sentence into words is to split

|

||

on spaces:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

words = corpus.split(' ')

|

||

words

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

['The', 'quick', 'brown', 'fox', 'jumps', 'over', 'the', 'lazy', 'dog']

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

## Bigrams

|

||

|

||

Now, we will want to create **bigrams**. A bigram is a pair of two words that

|

||

are in the order they appear in the corpus. To create bigrams, we will iterate

|

||

through the list of the words with two indices, one of which is offset by one:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

bigrams = [b for b in zip(words[:-1], words[1:])]

|

||

bigrams

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

[('The', 'quick'),

|

||

('quick', 'brown'),

|

||

('brown', 'fox'),

|

||

('fox', 'jumps'),

|

||

('jumps', 'over'),

|

||

('over', 'the'),

|

||

('the', 'lazy'),

|

||

('lazy', 'dog')]

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

How do we use the bigrams to predict the next word given the first word?

|

||

|

||

Return every second element where the first element matches the **condition**:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

condition = 'the'

|

||

next_words = [bigram[1] for bigram in bigrams

|

||

if bigram[0].lower() == condition]

|

||

next_words

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

['quick', 'lazy']

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We have now found all of the possible words that can follow the condition "the"

|

||

according to our corpus: "quick" and "lazy".

|

||

|

||

<pre>

|

||

(<span style="color:blue">The</span> <span style="color:red">quick</span>) (quick brown) ... (<span style="color:blue">the</span> <span style="color:red">lazy</span>) (lazy dog)

|

||

</pre>

|

||

|

||

Either "<span style="color:red">quick</span>" or "<span

|

||

style="color:red">lazy</span>" could be the next word.

|

||

|

||

## Trigrams and N-grams

|

||

|

||

We can partition our corpus into groups of threes too:

|

||

|

||

<pre>

|

||

(<span style="color:blue">The</span> <span style="color:red">quick brown</span>) (quick brown fox) ... (<span style="color:blue">the</span> <span style="color:red">lazy dog</span>)

|

||

</pre>

|

||

|

||

Or, the condition can be two words (`condition = 'the lazy'`):

|

||

|

||

<pre>

|

||

(The quick brown) (quick brown fox) ... (<span style="color:blue">the lazy</span> <span style="color:red">dog</span>)

|

||

</pre>

|

||

|

||

These are called **trigrams**.

|

||

|

||

We can partition any **N** number of words together as **n-grams**.

|

||

|

||

## Conditional Frequency Distributions

|

||

|

||

Earlier, we were able to compute the list of possible words to follow a

|

||

condition:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

next_words

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

['quick', 'lazy']

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

But, in order to predict the next word, what we really want to compute is what

|

||

is the most likely next word out of all of the possible next words. In other

|

||

words, find the word that occurred the most often after the condition in the

|

||

corpus.

|

||

|

||

We can use a **Conditional Frequency Distribution (CFD)** to figure that out! A

|

||

**CFD** can tell us: given a **condition**, what is **likelihood** of each

|

||

possible outcome.

|

||

|

||

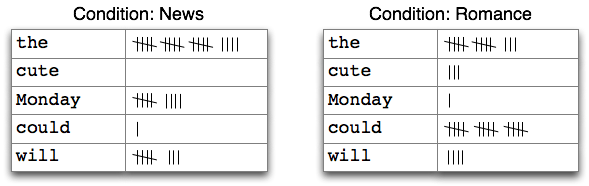

This is an example of a CFD with two conditions, displayed in table form. It is

|

||

counting words appearing in a text collection (source: nltk.org).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Let's change up our corpus a little to better demonstrate the CFD:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

words = ('The quick brown fox jumped over the '

|

||

'lazy dog and the quick cat').split(' ')

|

||

print words

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

['The', 'quick', 'brown', 'fox', 'jumped', 'over', 'the', 'lazy', 'dog', 'and', 'the', 'quick', 'cat']

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Now, let's build the CFD. I use

|

||

[`defaultdicts`](https://docs.python.org/2/library/collections.html#defaultdict-objects)

|

||

to avoid having to initialize every new dict.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

from collections import defaultdict

|

||

cfd = defaultdict(lambda: defaultdict(lambda: 0))

|

||

for i in range(len(words) - 2): # loop to the next-to-last word

|

||

cfd[words[i].lower()][words[i+1].lower()] += 1

|

||

|

||

# pretty print the defaultdict

|

||

{k: dict(v) for k, v in dict(cfd).items()}

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

{'and': {'the': 1},

|

||

'brown': {'fox': 1},

|

||

'dog': {'and': 1},

|

||

'fox': {'jumped': 1},

|

||

'jumped': {'over': 1},

|

||

'lazy': {'dog': 1},

|

||

'over': {'the': 1},

|

||

'quick': {'brown': 1},

|

||

'the': {'lazy': 1, 'quick': 2}}

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

So, what's the most likely word to follow `'the'`?

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

max(cfd['the'])

|

||

```

|

||

```python

|

||

'quick'

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Whole sentences can be the conditions and values too. Which is basically the way

|

||

[cleverbot](http://www.cleverbot.com/) works.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

## Random Text

|

||

|

||

Lets put this all together, and with a little help from

|

||

[nltk](http://www.nltk.org/) generate some random text.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

import nltk

|

||

import random

|

||

|

||

TEXT = nltk.corpus.gutenberg.words('austen-emma.txt')

|

||

|

||

# NLTK shortcuts :)

|

||

bigrams = nltk.bigrams(TEXT)

|

||

cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist(bigrams)

|

||

|

||

# pick a random word from the corpus to start with

|

||

word = random.choice(TEXT)

|

||

# generate 15 more words

|

||

for i in range(15):

|

||

print word,

|

||

if word in cfd:

|

||

word = random.choice(cfd[word].keys())

|

||

else:

|

||

break

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Which outputs something like:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

her reserve and concealment towards some feelings in moving slowly together .

|

||

You will shew

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Great! This is basically what the phone keyboard suggestions are doing. Now how

|

||

do we take this to the next level and generate text that looks like a poem?

|

||

|

||

## Random Poems

|

||

|

||

Generating random poems is accomplished by limiting the choice of the next word

|

||

by some constraint:

|

||

|

||

* words that rhyme with the previous line

|

||

* words that match a certain syllable count

|

||

* words that alliterate with words on the same line

|

||

* etc.

|

||

|

||

## Rhyming

|

||

|

||

### Written English != Spoken English

|

||

|

||

English has a highly **nonphonemic orthography**, meaning that the letters often

|

||

have no correspondence to the pronunciation. E.g.:

|

||

|

||

> "meet" vs. "meat"

|

||

|

||

The vowels are spelled differently, yet they rhyme [^1].

|

||

|

||

So if the spelling of the words is useless in telling us if two words rhyme,

|

||

what can we use instead?

|

||

|

||

### International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

|

||

|

||

The IPA is an alphabet that can represent all varieties of human pronunciation.

|

||

|

||

* meet: /mit/

|

||

* meat: /mit/

|

||

|

||

Note that this is only the IPA transcription for only one **accent** of English.

|

||

Some English speakers may pronounce these words differently which could be

|

||

represented by a different IPA transcription.

|

||

|

||

## Syllables

|

||

|

||

How can we determine the number of syllables in a word? Let's consider the two

|

||

words "poet" and "does":

|

||

|

||

* "poet" = 2 syllables

|

||

* "does" = 1 syllable

|

||

|

||

The vowels in these two words are written the same, but are pronounced

|

||

differently with a different number of syllables.

|

||

|

||

Can the IPA tell us the number of syllables in a word too?

|

||

|

||

* poet: /ˈpoʊət/

|

||

* does: /ˈdʌz/

|

||

|

||

Not really... We cannot easily identify the number of syllables from those

|

||

transcriptions. Sometimes the transcriber denotes syllable breaks with a `.` or

|

||

a `'`, but sometimes they don't.

|

||

|

||

### Arpabet

|

||

|

||

The Arpabet is a phonetic alphabet developed by ARPA in the 70s that:

|

||

|

||

* Encodes phonemes specific to American English.

|

||

* Meant to be a machine readable code. It is ASCII only.

|

||

* Denotes how stressed every vowel is from 0-2.

|

||

|

||

This is perfect! Because of that third bullet, a word's syllable count equals

|

||

the number of digits in the Arpabet encoding.

|

||

|

||

### CMU Pronouncing Dictionary (CMUdict)

|

||

|

||

A large open source dictionary of English words to North American pronunciations

|

||

in Arpanet encoding. Conveniently, it is also in NLTK...

|

||

|

||

### Counting Syllables

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

import string

|

||

from nltk.corpus import cmudict

|

||

cmu = cmudict.dict()

|

||

|

||

def count_syllables(word):

|

||

lower_word = word.lower()

|

||

if lower_word in cmu:

|

||

return max([len([y for y in x if y[-1] in string.digits])

|

||

for x in cmu[lower_word]])

|

||

|

||

print("poet: {}\ndoes: {}".format(count_syllables("poet"),

|

||

count_syllables("does")))

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Results in:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

poet: 2

|

||

does: 1

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

## Buzzfeed Haiku Generator

|

||

|

||

To see this in action, try out a haiku generator I created that uses Buzzfeed

|

||

article titles as a corpus. It does not incorporate rhyming, it just counts the

|

||

syllables to make sure it's [5-7-5]((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haiku). You can view the full code

|

||

[here](https://github.com/thallada/nlp/blob/master/generate_poem.py).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Run it live at:

|

||

[http://mule.hallada.net/nlp/buzzfeed-haiku-generator/](http://mule.hallada.net/nlp/buzzfeed-haiku-generator/)

|

||

|

||

## Syntax-aware Generation

|

||

|

||

Remember these?

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Mad Libs worked so well because they forced the random words (chosen by the

|

||

players) to fit into the syntactical structure and parts-of-speech of an

|

||

existing sentence.

|

||

|

||

You end up with **syntactically** correct sentences that are **semantically**

|

||

random. We can do the same thing!

|

||

|

||

### NLTK Syntax Trees!

|

||

|

||

NLTK can parse any sentence into a [syntax

|

||

tree](http://www.nltk.org/book/ch08.html). We can utilize this syntax tree

|

||

during poetry generation.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

from stat_parser import Parser

|

||

parsed = Parser().parse('The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.')

|

||

print parsed

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Syntax tree output as an

|

||

[s-expression](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S-expression):

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

(S

|

||

(NP (DT the) (NN quick))

|

||

(VP

|

||

(VB brown)

|

||

(NP

|

||

(NP (JJ fox) (NN jumps))

|

||

(PP (IN over) (NP (DT the) (JJ lazy) (NN dog)))))

|

||

(. .))

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

parsed.pretty_print()

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

And the same tree visually pretty printed in ASCII:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

S

|

||

________________________|__________________________

|

||

| VP |

|

||

| ____|_____________ |

|

||

| | NP |

|

||

| | _________|________ |

|

||

| | | PP |

|

||

| | | ________|___ |

|

||

NP | NP | NP |

|

||

___|____ | ___|____ | _______|____ |

|

||

DT NN VB JJ NN IN DT JJ NN .

|

||

| | | | | | | | | |

|

||

the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog .

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

NLTK also performs [part-of-speech tagging](http://www.nltk.org/book/ch05.html)

|

||

on the input sentence and outputs the tag at each node in the tree. Here's what

|

||

each of those mean:

|

||

|

||

|**S** | Sentence |

|

||

|**VP** | Verb Phrase |

|

||

|**NP** | Noun Phrase |

|

||

|**DT** | Determiner |

|

||

|**NN** | Noun (common, singular) |

|

||

|**VB** | Verb (base form) |

|

||

|**JJ** | Adjective (or numeral, ordinal) |

|

||

|**.** | Punctuation |

|

||

|

||

Now, let's use this information to swap matching syntax sub-trees between two

|

||

corpora ([source for the generate

|

||

function](https://github.com/thallada/nlp/blob/master/syntax_aware_generate.py)).

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

from syntax_aware_generate import generate

|

||

|

||

# inserts matching syntax subtrees from trump.txt into

|

||

# trees from austen-emma.txt

|

||

generate('trump.txt', word_limit=10)

|

||

```

|

||

```

|

||

(SBARQ

|

||

(SQ

|

||

(NP (PRP I))

|

||

(VP (VBP do) (RB not) (VB advise) (NP (DT the) (NN custard))))

|

||

(. .))

|

||

I do not advise the custard .

|

||

==============================

|

||

I do n't want the drone !

|

||

(SBARQ

|

||

(SQ

|

||

(NP (PRP I))

|

||

(VP (VBP do) (RB n't) (VB want) (NP (DT the) (NN drone))))

|

||

(. !))

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Above the line is a sentence selected from a corpus of Jane Austen's *Emma*.

|

||

Below it is a sentence generated by walking down the syntax tree and finding

|

||

sub-trees from a corpus of Trump's tweets that match the same syntactical

|

||

structure and then swapping the words in.

|

||

|

||

The result can sometimes be amusing, but more often than not, this approach

|

||

doesn't fare much better than the n-gram based generation.

|

||

|

||

### spaCy

|

||

|

||

I'm only beginning to experiment with the [spaCy](https://spacy.io/) Python

|

||

library, but I like it a lot. For one, it is much, much faster than NLTK:

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

[https://spacy.io/docs/api/#speed-comparison](https://spacy.io/docs/api/#speed-comparison)

|

||

|

||

The [API](https://spacy.io/docs/api/) takes a little getting used to coming from

|

||

NLTK. It doesn't seem to have any sort of out-of-the-box solution to printing

|

||

out syntax trees like above, but it does do [part-of-speech

|

||

tagging](https://spacy.io/docs/api/tagger) and [dependency relation

|

||

mapping](https://spacy.io/docs/api/dependencyparser) which should accomplish

|

||

about the same. You can see both of these visually with

|

||

[displaCy](https://demos.explosion.ai/displacy/).

|

||

|

||

## Neural Network Based Generation

|

||

|

||

If you haven't heard all the buzz about [neural

|

||

networks](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_neural_network), they are a

|

||

particular technique for [machine

|

||

learning](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machine_learning) that's inspired by our

|

||

understanding of the human brain. They are structured into layers of nodes which

|

||

have connections to other nodes in other layers of the network. These

|

||

connections have weights which each node multiplies by the corresponding input

|

||

and enters into a particular [activation

|

||

function](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activation_function) to output a single

|

||

number. The optimal weights for solving a particular problem with the network

|

||

are learned by training the network using

|

||

[backpropagation](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backpropagation) to perform

|

||

[gradient descent](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gradient_descent) on a

|

||

particular [cost function](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_function) that

|

||

tries to balance getting the correct answer while also

|

||

[generalizing](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regularization_(mathematics)) the

|

||

network enough to perform well on data the network hasn't seen before.

|

||

|

||

[Long short-term memory

|

||

(LSTM)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_short-term_memory) is a type of

|

||

[recurrent neural network

|

||

(RNN)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recurrent_neural_network) (a network with

|

||

cycles) that can remember previous values for a short or long period of time.

|

||

This property makes them remarkably effective at a multitude of tasks, one of

|

||

which is predicting text that will follow a given sequence. We can use this to

|

||

continually generate text by inputting a seed, appending the generated output to

|

||

the end of the seed, removing the first element from the beginning of the seed,

|

||

and then inputting the seed again, following the same process until we've

|

||

generated enough text from the network ([paper on using RNNs to generate

|

||

text](http://www.cs.utoronto.ca/~ilya/pubs/2011/LANG-RNN.pdf)).

|

||

|

||

Luckily, a lot of smart people have done most of the legwork so you can just

|

||

download their neural network architecture and train it yourself. There's

|

||

[char-rnn](https://github.com/karpathy/char-rnn) which has some [really exciting

|

||

results for generating texts (e.g. fake

|

||

Shakespeare)](http://karpathy.github.io/2015/05/21/rnn-effectiveness/). There's

|

||

also [word-rnn](https://github.com/larspars/word-rnn) which is a modified

|

||

version of char-rnn that operates on words as a unit instead of characters.

|

||

Follow [my last blog post on how to install TensorFlow on Ubuntu

|

||

16.04](/2017/06/20/how-to-install-tensorflow-on-ubuntu-16-04.html) and

|

||

you'll be almost ready to run a TensorFlow port of word-rnn:

|

||

[word-rnn-tensorflow](https://github.com/hunkim/word-rnn-tensorflow).

|

||

|

||

I plan on playing around with NNs a lot more to see what kind of poetry-looking

|

||

text I can generate from them.

|

||

|

||

---

|

||

|

||

[^1]:

|

||

Fun fact: They used to be pronounced differently in Middle English during

|

||

the invention of the printing press and standardized spelling. The [Great

|

||

Vowel Shift](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Vowel_Shift) happened

|

||

after, and is why they are now pronounced the same.

|